The central focus of this course is understanding and applying the principles of visual rhetoric. You are expected to read and write and think in order to complete the work assigned. To be successful, you should read and write and think about visual rhetoric every day.

In general, I expect you to understand the material and the assigned resources without my having to repeat it in class; however, please feel free to ask for further explanation. (Students who do poorly in my courses tend to review the resources in a cursory fashion and fail to take advantage of opportunities to ask questions.)

For me, and, therefore, in this course, successful learning circulates publicly, for learning - like writing - is inherently social. Learning, especially in academics, is at its best when it is enriched by our reading and part of a larger, informed conversation among intellectual peers. Our class will participate in these types of conversations about visual rhetoric throughout the semester, sharing our ideas and circulating our work inside and outside the classroom.

As bright, articulate, and contributing members to the intellectual world at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, your responsibility is to participate in the conversations that are going on in the various intellectual communities on campus. And reading and writing, in all forms and genres, is the primary means of scholarly communication. In this course, I will provide you with the spaces and the tools to continue to develop your intellectual skills. But YOU must make the choice, and take the responsibility for that choice, to engage with the course materials and with your classmates in this course.

Our course is comprised of range of activities. While each of the activities is unique, and while each will help you develop your understanding of visual rhetoric in different ways, all of the activities will follow a predictable, process/procedure:

- Introduction to the concept/activity/project, which will require reviewing the resources

- Discussion of the concept/activity/project, both in class and on course discussion boards

- Review of examples to enhance your understanding of the concept/activity/project

- Drafting materials for the concept/activity/project

- Negotiation of the criteria for evaluating the work associated with the concept/activity/project

- Peer review of drafts

- Revision of the materials for the concept/activity/project

- Opportunity for feedback from the instructor

- Reflecting on the work performed and your development in understanding visual rhetoric

- Submission of materials

Most importantly, you are expected to ask questions any time you are uncertain of what is required of you or any time you do not understand the materials.

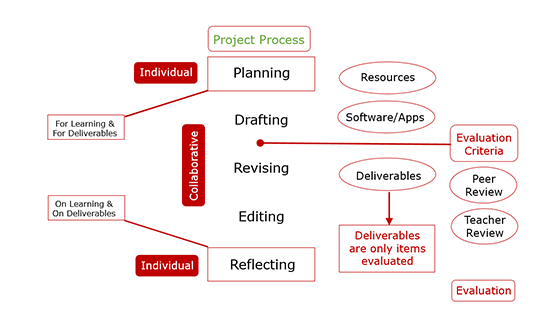

To break this down further, we start with a basic template for all projects:

|

|

|

Working from left to right and top to bottom, you can see that I will provide initial readings to get you started toward achieving the initial project aims. And I use the word initial quite consciously because I expect you to take control of the projects and develop them to fit your learning goals. In all of the projects, every each of you will contribute resources, you will use and review software or apps that are relevant to a particular project and share your experiences with the rest of the class, and you will define and construct deliverables that build your competencies for visual rhetorical practice in general, as well as to meet the project aims.

Returning to the graphic, I will next describe the project process more fully. This process is important because it helps me to build in the time necessary for students to work, to play, to make mistakes, to share, to collaborate: to learn. I especially want to promote informal learning opportunities by giving you that time, but also giving you credit for participating in the class, contributing whatever you can to the course's success, for just showing up.

The project process begins with an enhanced version of a traditional writing process. That traditional model was primarily individual, primarily linear. But I want to think of our projects as cognitive process and social practice.

As cognitive process, our projects (like students' learning) are developmental and recursive. Considered developmentally, I can describe our projects as evolving through these stages, but I expect it to be recursive, not linear: learners move back and forth among the stages as they work toward submission of project deliverables. As social practice, I want you to engage with the class, to share knowledge and ask questions, to be sensitive to your own learning needs while, at the same time, contributing to the larger ongoing conversations. This open atmosphere is designed to help you learn about and learn how to choose and use a wide range of strategies that will aid in your critical learning and reflective practices. I want you to personalize your experience with each project, to develop from where you are at, currently, in your thinking and skill level.

The planning stage and the reflecting stage should be a time when you can articulate what you want to learn and how you will do it. I want the projects to be purposeful, to have meaning to you so you engage with the work (even if it's purely for your own reasons), so you feel like you are accomplishing things, DOING something. But, for me, your work should not be limited to just the deliverables, which soon would become merely artifacts for a course, rather than models for lifelong learning, participation on multiple levels in an active constructive process.

While I want you to look inward for your learning goals, I also expect outward participation, as well. At the early stages of any project, you should be gathering resources for understanding concepts more fully and for completing the work. You should be exploring and reviewing uses for different software or apps that will help you construct more effective deliverables. And you should be beginning to draft materials for those deliverables.

These early stages are designed to help you explore and establish a context for the project, so you understand it well enough to begin to discuss how your work should be evaluated. At this point, we will develop the evaluation criteria as a class. This includes an explicit understanding that part of your reflection should address the ways that you have met the criteria relative to their own learning goals for the project.

Once the evaluation criteria is negotiated and agreed upon, drafts of the deliverables can be completed, for the first time. On this side of the project, your work will go through multiple drafts, with time set aside for peer review and teacher review before you submit your work for evaluation. The goal here is to model recursivity, to encourage trust in multiple perspectives, to allow for the time necessary to submit quality materials.

Part of these discussions will focus on performing higher-order revisions and lower-order edits before you submit a deliverable for evaluation. And the deliverables are the only items evaluated. As I stated earlier, the majority of your work is participatory, a contribution to your own learning and to the learning of your classmates. As you can imagine, the key to all of this is time. I will do my best to be patient and provide the time for you to explore, the time to experiment, the time to fail, before you make the move to final completion. I look forward to seeing what you will accomplish.

I'm hoping that you can see that this project design template, with your help, seeks to create and maintain flexible curricula and relevant assets within a networked learning environment that encourages a more collaborative approach, one that privileges informal and situated learning, and promotes ubiquitous and lifelong learning, thereby increasing learner control, learner choice, and learner independence.